A Possible New Backend for Rust

So typically when you want to make your own compiled language you need a compiler to.. well.. compile it into something useful. Then making it work across a wide range of operating systems and CPU architectures is a huge effort, let alone having it be performant. This is where LLVM comes in.

You can scan through your source code, parse it into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) then generate some abstract language (let’s call this Intermediate Representation) which LLVM can understand, LLVM says “Thanks! We’ll take it from here”.

So as long as you can generate something LLVM understands, it can make fast binaries for you, and that’s the advantage; you focus on your syntactical analysis, they focus on generating fast executables.

Rust, C, C++, Swift, Kotlin and many other languages do this and have been doing so for years. Often it’s achieved by having some component that generates LLVM IR.

Is that a compiler backend or frontend?

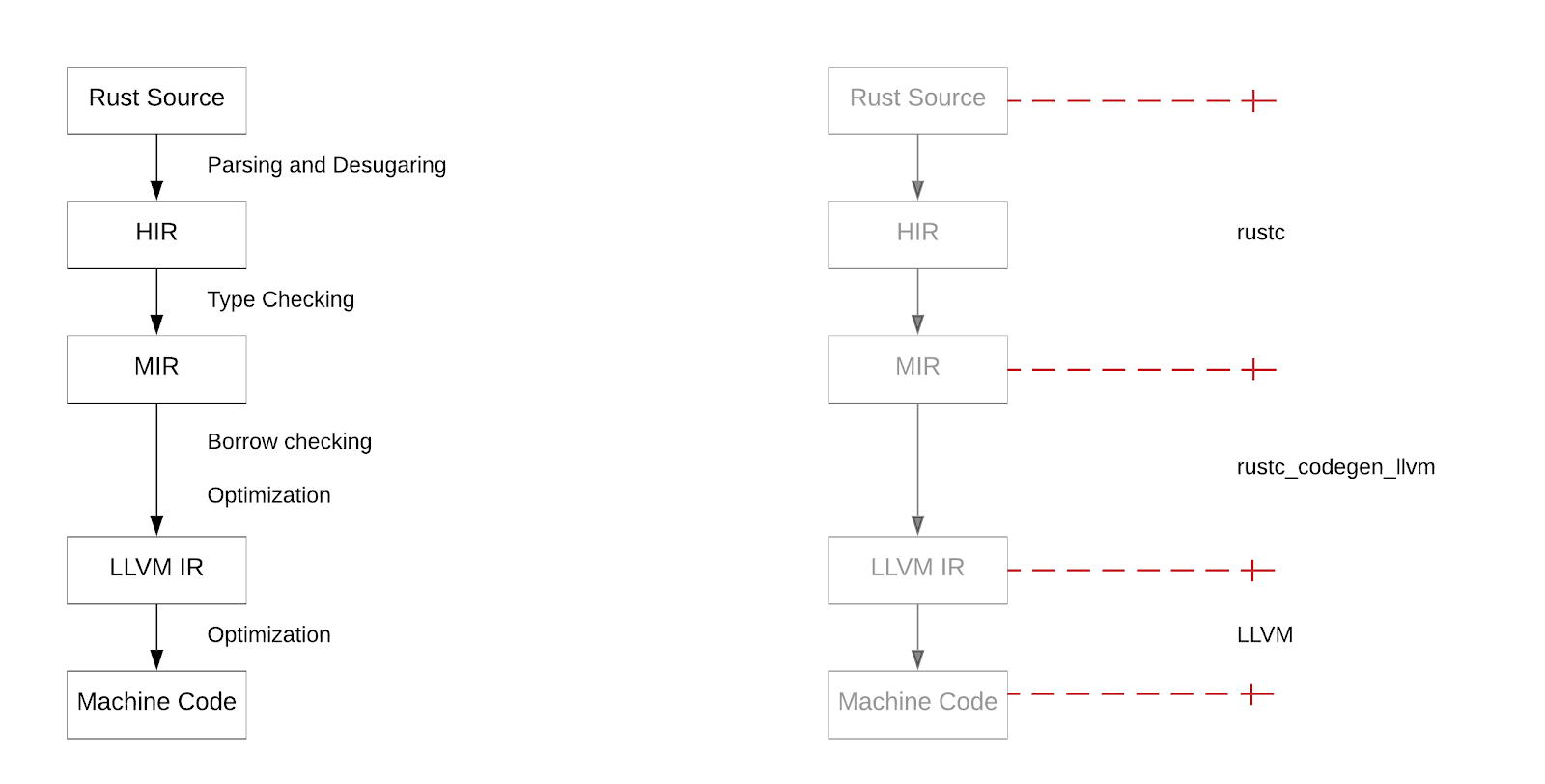

In Rust, rustc is the main compiler which your source code is fed into first, it does things a typical compiler would do like generate an AST (in this context we call a High-Level Representation, or HIR for short). Once in tree-form type checking and other tasks can be performed then it’s compiled down to another representation ready for whichever backend takes it. The default backend of rustc is called rustc_codegen_llvm (or cg_llvm) which itself also acts as a front end to LLVM.

To make the above more clear, I’ve taken the chart from the 2016 MIR blog post and annotated the responsibilities over it.

From a high level that’s the architecture of Rust in 2020. I say “high level” because the space between LLVM IR and Machine Code alone has multiple steps of compilation and that’s where a chunk of time can go.

Compared to Go, Rust hasn’t been the fastest to compile. Incremental compilation helped a lot but cold-cache builds suffer.

Because LLVM is so efficient at making fast/optimised binaries it’s inefficient at making slow/cheap ones, even with optimisations turned off you still end up with a slow compile and a some-what fast executable. Apart from being a good problem to have it can be a real problem for development because while you’re fixing that bug or testing a function you want quick feedback, and this has irked seasoned rustaceans for some time plus put off new ones.

Compiling development builds at least as fast as Go would be table stakes for us to consider Rust_

Rust Survey 2019

The dilemma starts to compound when you realise LLVM was also designed around compiling C/C++ more than anything else, even an IR needs to come from something and why not use an existing language to model it ?

There seems to be no accurate & explicit specification of the semantics of infinite loops in LLVM IR. It aligns with the semantics of C++, most likely for historical reasons and for convenience

Cranelift

Meanwhile, there exists Cranelift, a [machine] code generator written in Rust developed by the Bytecode Alliance8.

It generates code for WebAssembly and replaces the optimizing compiler in Firefox. It was designed to generate code fast (using parallelism) but is generic enough to be a compile target, meaning just like LLVM you can compile any language to its IR and have it do the rest.

The idea of using it for Rust has floated around for years, and why not? It introduces some healthy competition on the backend, is defined for speedy compilation and the Rust team (plus Mozilla) would be able to help steer the design goals. There’s also the added bonus of giving rustaceans an all-rust compiler for the first time compared to the Rust/C++ hybrid that exists today.

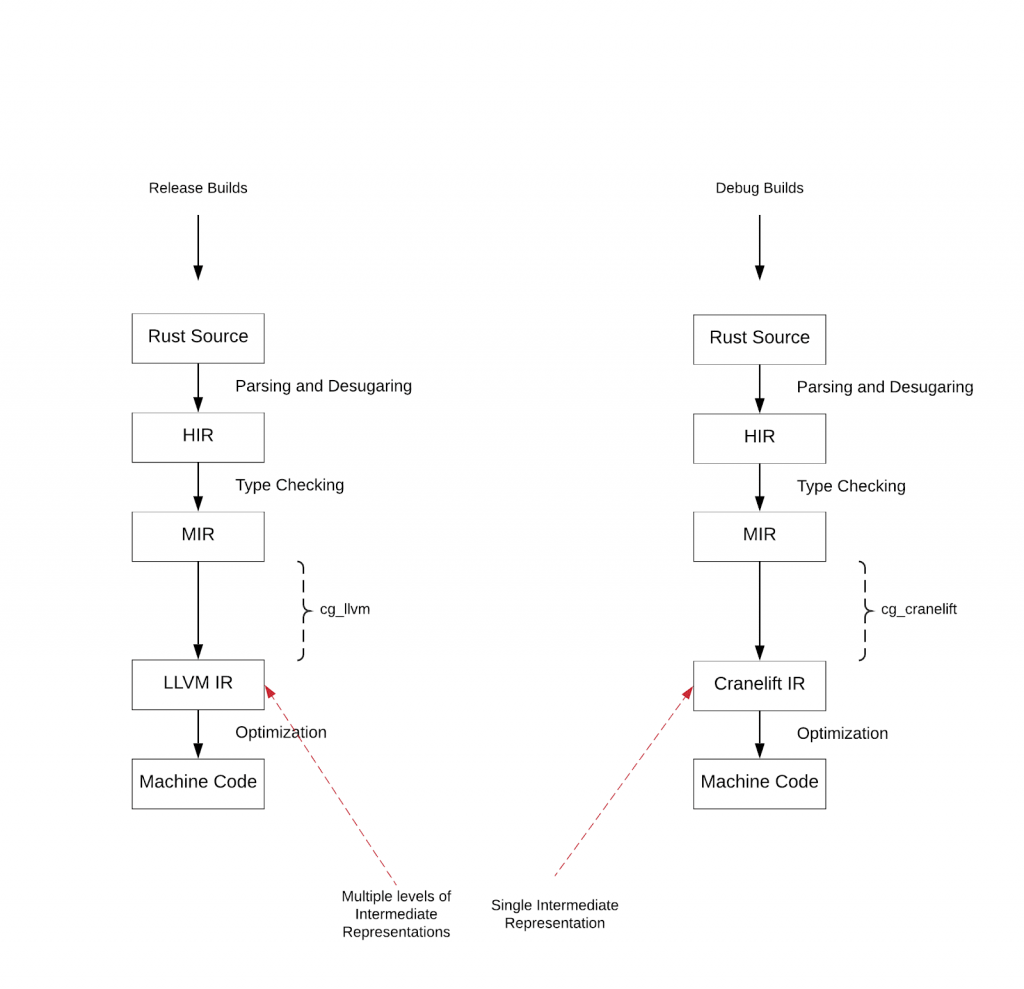

Of course, Cranelift may not be able to catch-up with LLVM’s optimizations and support for all those architectures, but using it for debug builds could prove useful.

One of the things is that LLVM has several layers of IR while Cranelift has only one. Another is that Cranelift does use a graph coloring register allocator, but simply a dumber one, thus being faster.

That’s Bjorn3, he decided to experiment in this area whilst on a summer vacation, and a year & half later single-handedly (bar a couple of PRs) achieved a working Cranelift frontend. The effort here cannot be understated, this is usually the work of an entire team not a curious student in his spare time. There’s worry about the high bus-factor but I can imagine this made the initial development process faster.

I have the freedom to change what I want whenever I want. Sometimes there are problems I can’t solve myself though as I am not familiar enough with the respective area. For example object files, linkers and DWARF debuginfo. Luckily I know people who do know a lot about those things.

So rustc_codegen_cranelift (cg_clif for short) exists and has existed quietly in the background for some time, not only it proved worthwhile as a proof-of-concept, it exceeded expectations. In 2018 measurements showed it being 33% faster to compile. In 2020 we’re seeing anything from 20-80% depending on the crate.11 That’s an incredible feat considering there are more improvements in sight.

There are bits and pieces missing, such as partial SIMD support, ABI Compatibility, unsized values and many more. There’s also lack of feature parity with Cranelift itself, such as cg_clif being blocked because Cranelift doesn’t support a feature LLVM does. However, these problems are shrinking and most crates do build today.

Bringing this together

In April 2020, the rust compiler team decided to catch up with bjorn3 and add cg_clif as a git subtree and “gate on builds”. This means the rust compiler will build against both the LLVM and Cranelift backends then fail the build should either of them not work properly.

cg_clif can be worked on independently whilst having the wider team build against changes whenever they decide to pull in updates.

Although this does not mean the Rust compiler team are officially supporting a Cranelift build, it does offer a step forward for the ecosystem to start thinking about an LLVM/Cranelift future. For instance, the compiler team tested some LLVM features directly, these obviously fail in the Cranelift build, now some thought is put into separating these tests out or at least marking them as “LLVM specific” so other backends can be tested properly.

Below shows the ambition some rustaceans would like to get towards.

Benchmarks

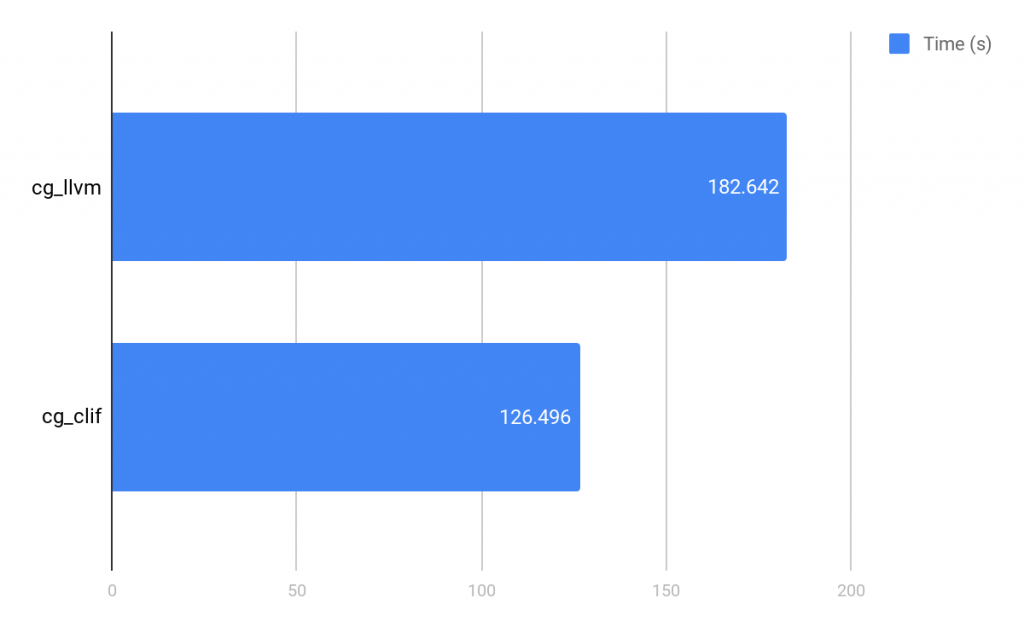

The corpus used for this benchmark is a checkout of Boa specifically commit 8002a95, a built checkout of rustc_codegen_cranelift (8002a95) and rustc 1.44.0-nightly.

This machine is an AMD Ryzen 7 2700X 3.70GHz, 16 CPUs, 32GB memory and an SSD, however, these are running in a container which only has access to 12 CPUs & 12GB memory.

Hyperfine was used with 10 runs of both backends, cargo cleaning between each run.

This benchmark compares the time it takes to build Boa.

The Cranelift backend is a clear winner, knocking off almost a whole minute of build times. I was expecting around 20-30s before running this, so a delta of 56s was quite significant.

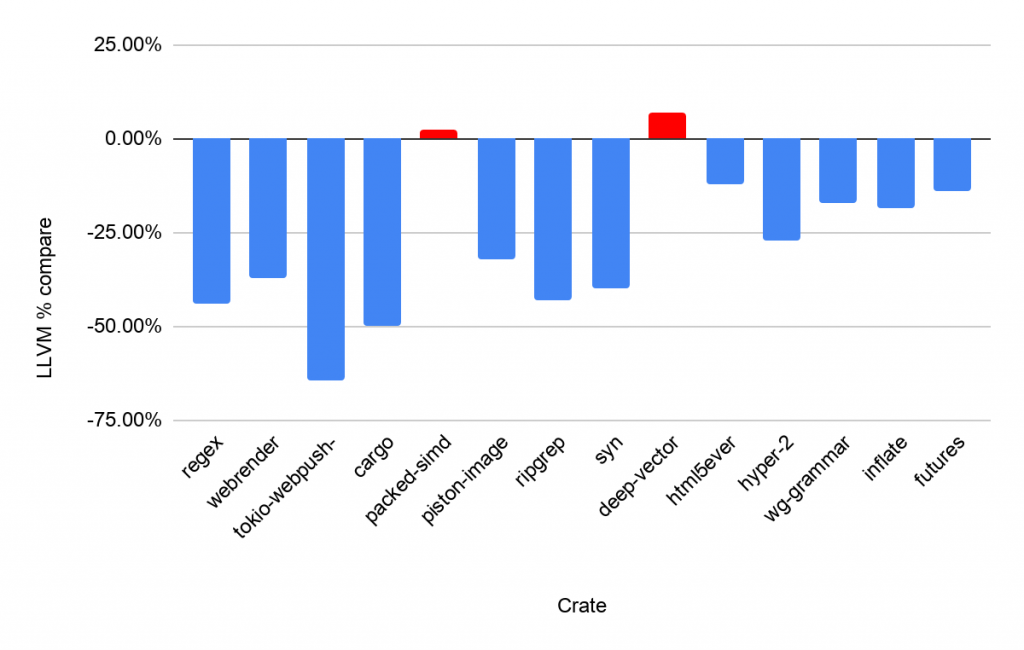

The next set of benchmarks were run on a laptop with an Intel® Core™ i3-7130U CPU @ 2.70GHz and an SSD. This gives a more broad view of some popular rust packages being compiled from an empty cache. We’re comparing the avg time to build compared to cg_llvm so 0% would mean they’re the same.

Builds times (cg_llvm baseline)

SIMD support is only partial so that could explain packed-simd and deep-vector but we don’t know that for sure. However on the whole most packages will build faster than they do today. The average improvement today is still around 30% but I’m sure results will only improve as time goes on.

Conclusion

Overall, it’s quite exciting to have a new backend to help with debug builds by delivering much faster build times. The benchmark results look promising and its clear more communication between cg_clif, rustc and cranelift is now happening.

Help is certainly needed. https://github.com/bjorn3/rustc_codegen_cranelift is where the bulk of development is happening, the readme has improved since my first glance. You can run your own benchmarks using a tool like Hyperfine.

The next step on from that would be filing an issue if you come across any problems, or diving into the issues that are already available.

Cranelift parity is also important to unblocking cg_clif, so improvements there are still needed.

With all that being said, a new backend could be one of the most interesting developments this year.